Racism and redlining have profoundly impacted individuals and their communities. Millions of individuals face difficulties every day from disparities in quality of life caused by systemic racism and discriminatory practices such as redlining, making it much more difficult for citizens to receive critical services. Ethnic groups targeted by discriminatory policies often suffer from chronic diseases, infection, and premature mortality. Beyond individual health, however, these injustices wear down local job growth, stifle business development, lower employment opportunities, and weaken the foundation of these communities.

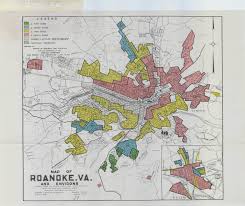

Discriminatory practices and the echoes of redlining continue to have prominent repercussions for many individuals that continue to shape neighborhoods. Redlining, implemented in the 1930’s, involved the Federal Housing Association (FHA), set up by the U.S. government to encourage home ownership during the Great Depression, offering substantial loans and mortgages (De Los Santos et al.). However, to maximize the benefits and revenue to the economy, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal program also created during this time period, chose which neighborhoods should get the aforementioned services, and which ones should not receive them. Race was a key factor during evaluations, favoring white neighborhoods which as a result were more commonly offered mortgages and loans by the government, while those with minorities, such as in Italian and Black communities, often received none. This exclusion by the government entrenched poverty in many families and individuals with minimal access to money or outside financial sources, leading to systemic and widespread legacy of poverty and low-income wages prevalent today in minority communities of cities such as Chicago, Washington D.C, and Baltimore. For example, 20% of Bronx residents, primarily Latinos, lack insurance, increasing vulnerability to chronic diseases and premature mortality (Hartnett). Furthermore, formerly racially segregated communities are more susceptible to health crises like Covid-19, which killed millions across the United States (Magesh et al.). HOLC maps discouraged contractors, developers and investors in “low grade” areas, cutting access from essential services such as hospitals, shelters and emergency care. The xenophobic system left ethnic communities to disproportionately struggle with socioeconomic and health inequalities.

Redlining and prejudiced policies continue to complicate the lives of many individuals, particularly in health quality. Access to healthcare services and well-paying jobs is crucial in ensuring the quality of life in America, yet many locations do not have access to these bare minimums. Historically discriminated individuals, whether affected by redlining or being descended from slaves, are disproportionately affected, and lack essential services necessary for a high quality of life. In Chicago, Hispanics and Black Americans have the lowest life expectancy, with Latinos averaging 80 years and African Americans only 71.4 (Chicago Department of Public Health, 2021). The median age has been steadily decreasing since 2012 for the Windy City, in contrast to the national average, which has been increasing. Garfield Park, listed as Fourth Grade and Third Grade by the HOLC, demonstrates the long term effects of redlining. D25, a ward within Garfield Park, has a life expectancy hovering just above 65 years, and poverty at a high 31.1%. Obesity is a daily burden for 46.6% of the population, primarily among the 87.3% minority group population, many descended from generations of Italian immigrants and Black Americans (University of Richmond). Just a few miles away, D36, originally settled by both Italians and Jews also encompasses the long term consequences of redlining. Illicit dumping causes existing properties to devalue even more, leading to poverty rates of over 51%, and nearly 20% of individuals suffer from diabetes. Mental health issues are also common, ranging around 21.7% (University of Richmond). In Detroit, a city rooted with a similar origin of manufacturing and industry, also demonstrates the effects of redlining similarly. Factory and plant closures, particularly in the automotive industry over the past 30 years have placed a heavy burden on low and middle class workers, often from ethnic groups excluded from government aid and financial investments. Redlining made working families dependent upon high labor jobs, often risky, which vanished following economic turmoils such as the 2007-2009 recession. D24, a precinct rooted in Polish origins rated as fourth grade by the HOLC, struggles with a high poverty rate of 60.4%, and a median age of just 25 (University of Richmond). Similar patterns prevail in many cities and suburbs, whether it is Baltimore, Boston or Birmingham. The lack of government support and inaccessible loans created widespread dependence upon transient factory jobs for companies like Chrysler and General Motors, both of which closed plants in Detroit in 2008, further negating the quality of life for many who depended upon those jobs for their paycheck or insurance.

From redlining to segregation, historical racism in legislation, law and government have negatively impacted communities and individuals in health, economic, and social aspects. Americans and many immigrants living in “undesirable” neighborhoods experience poor health outcomes, including being more likely to suffer from diabetes, obesity, and cancer. However, profound effects go beyond health in these communities, as these areas suffer from the lack of modernization, stagnant job growth, and high crime rates. For instance, a study by the US Census Bureau, highlighted by the Chicago Department of Health Services, found that over 60% of Garfield Park residents do not have access to modern broadband internet (United States Census Bureau, 2017). While this may not seem perilous, it is in fact significant, as access to high speed internet greatly improves communication, civic engagement, access to health services and the pursuit of education, all of which contribute to longer, higher quality lives. Unfortunately, individuals in these communities continue to experience racism at the hands of the police. In Chicago, 60% of stops conducted by police officers target Black individuals, compared to 21% for Latinos and just 15% to Whites. Similarly, searches and citations are also the highest for Black individuals, at 58% and 48% respectively (Goudie et al.) Food insecurity is another major component of interconnectedness between redlining, racism, health and socioeconomics. Minority Black communities continue to face the most severe lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables. For example, South Deering, Chicago, has a staggering disparity in access to fresh food, with over 57.2% of citizens, majority Black and Hispanic, living there having to commute more than ½ mile away from a store selling such produce, despite the area’s high density population (United States Department of Agriculture). Among leading reasons for why residents do not purchase healthier options, 62.4% interviewed claimed that it costs too much. Additionally, Latinos experience the lowest access to quality, unprocessed food at a mere 46.2% (Chicago Health Atlas, 2025). Finally, affordable housing continues to be a major problem for many. A study conducted by the Metropolitan Planning Council found that neighborhoods that need affordable housing the most do not have access to it. North Lawndale has less than 2.5% affordable housing units, despite over 40.3% of land parcels being foreclosed between 2005 and 2013 (Metropolitan Planning Council). From policing to food access to affordable housing, all these socioeconomic factors present underscore systematic inequalities, and how the system keeps oppression in place. Minority groups continue to suffer from disparities in health equity and wealth, all while wealthy investors continue to pour millions into Chicago’s downtown area for luxury developments, reinforcing the long standing social divides of Chicago, and those of many cities across the United States.

Redlining and xenophobia have shaped the United States in ways beyond imagination. Countless citizens suffer from the negligence and hate of America’s establishment. Redlining and other discriminatory practices have contributed to making targeted individuals at greater risks for many issues, ranging from chronic diseases, to obesity, to unemployment, police brutality, and lack of economic prosperity. The cycle of hardship for countless individuals remains unbroken. The United States is getting closer to breaking that chain, but it is critical that leaders and residents of communities across the entire nation work together, fight for change and solutions in unity. Civil rights have been won. Disability rights have been won. This fight also needs to be won.

Works Cited

Chicago Department of Public Health. The State of Health for Blacks in Chicago. 2021.

De Los Santos, Hannah, et al. “From Redlining to Gentrification: The Policy of the Past That Affects Health Outcomes Today.” Info.primary care.hms.harvard.edu, 26 May 2021, info.primarycare.hms.harvard.edu/perspectives/articles/redlining-gentrification-health-outcomes.

“Easy Access to Fruits and Vegetables Rate | Chicago Health Atlas.” Chicago Health Atlas, 2025, chicagohealthatlas.org/indicators/HCSFVAP?tab=chart. Accessed 21 Apr. 2025.

“Experience.” Gisportal.ers.usda.gov, gisportal.ers.usda.gov/portal/apps/experiencebuilder/experience/?id=a53ebd7396cd4ac3a3ed09137676fd40&page=Introduction.

Hartnett, Kara. “How Health Inequity Maps out across America.” Modern Healthcare, 22 Feb. 2023, www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/health-equity-america-cdc-social-vulnerability-index-evangeline-parish-bronx-county-navajo-county.

Goudie, Chuck, et al. “Chicago Police More Likely to Stop Black Drivers without Citing Them, Data Investigation Reveals.” ABC7 Chicago, 9 Sept. 2020, abc7chicago.com/chicago-police-racial-profiling-traffic-stops-department/6416266/.

Housing Affordability, Zoning, and the Creation of a Chicago Open to All Residents. Nov. 2024.

Magesh, Shruti, et al. “Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status.” JAMA Network Open, vol. 4, no. 11, 11 Nov. 2021, p. e2134147, jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2785980.

“Not Even Past: Social Vulnerability and the Legacy of Redlining.” Dsl.richmond.edu, dsl.richmond.edu/socialvulnerability/map/#loc=11/41.873/-87.714&city=chicago-il.

United States Census Bureau. “2013-2017 ACS 5-Year Estimates.” The United States Census Bureau, 28 Nov. 2018, www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2017/5-year.html.