As schools become political fighting grounds–fueled by COVID policies and concerns about censorship–book challenges have been increasing rapidly. In the Bedford School District alone, six books have been challenged just this year.

The school district’s current plan for book challenges is to form a committee, headed by Assistant Superintendent Tom Laliberte, which includes the media specialist from the school as well as their principal, two citizens, and one other employee of the district–the Dean of Humanities, Mrs. O’Hara, who stepped in for the book challenge at the high school. The committee has twenty days to read the book and submit a decision to the superintendent, Mr. Fournier. The disputed book will remain on the shelves until the decision is made. School board member Mr. Schneller attempted to change this policy into the new procedure of removing a book as soon as it is challenged. This proposal arose from concerns that the time between challenge and decision would increase with the number of book challenges, allowing the content to be available to students for an extended period of time. Ultimately, Mr. Schneller’s proposal was voted against, and the current policy remains standing. All six book review committees have been able to finish in time.

Each of the committees formed to review the six challenged books–one at BHS and five at McKelvie–determined that the books were valuable and should remain on the shelves. At the high school, Lawn Boy was challenged. This book is a coming-of-age novel about a man reflecting on his self-discovery that investigates stereotypes about race, class, and LGBTQ relationships. The committee decided to keep the book on the shelves, but the same parent appealed the decision to the School Board. On January 26th, they met with Mrs. Gilcreast and the school board members voted 2-1 to keep the book, agreeing with the committee’s decision, although the School Board members were not required to read the book prior to this determination. One member abstained and one was absent during the vote.

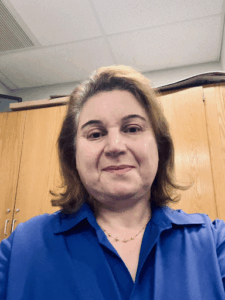

Although Mrs. Gilcreast’s experience with book challenges began this year, her history with defending children’s rights to read and see themselves reflected in books has not. She currently holds the position as the Intellectual Freedom Chair for the Board for the NH School Library Media Association. She was on the Conference Chair for many years beforehand, stepped back from the board for a short time, and then returned to become the Chair once book challenges increased across the country.

Mrs. Gilcreast’s position is to be a support system for other librarians in the state if they experience any media challenges–an increasingly important role. Citizens have a legal right to challenge any materials in a library and Mrs. Gilcreast’s position allows her to support the librarian with any resources and information on how to handle the book challenge, as well as advise on library procedures like book selection and weeding.

When asked how she felt about the book challenges districtwide this year, Mrs. Gilcreast described her disappointment in watching the carefully selected materials be challenged. In addition, she explains that the LGBTQ club told her that they felt underrepresented in the library, so she added Lawn Boy–an Alex Award Winner, a national recognition, rated for the high school age and stage, despite the difficult content it deals with. This was just one of Mrs. Gilcreast’s attempts to choose materials in conjunction with the wants and needs of students and teachers.

Mrs. Gilcreast became emotional as she described that her purpose is to offer students “windows and mirrors into other people’s lives”: the chance to see themselves reflected in books but also the opportunity to look into someone else’s life. She went on to say that although some content and experiences are hard to deal with, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t learn from them and understand the perspectives of other people. These types of books teach empathy and compassion to teenagers. Mrs. Gilcreast stressed the importance of reading novels that deal with difficult topics and complex issues, especially as a student living in a small New England town that has a limited range of diversity and experiences.

Mrs. Gilcreast then went on to describe her concerns about the number of book challenges, particularly in contrast to past years: “If this one book is removed from the shelves, what does that open us up to?” She acknowledged that not every book is right for every student, especially the ones that deal with hard topics like Lawn Boy, and that is why libraries give students the freedom to put the book down.

In addition to the censorship brought by these book challenges, Mrs. Gilcreast described the immense amount of added work that these committees bring. In her fifteen years as a librarian, she has yet to have a book challenge before this year as this job brings extra reading and preparation- she has to make sure that she is ready to have difficult conversations and prove that she has followed district procedures. Mrs. Gilcreast dedicated months and uncountable hours to educating herself on how to deal with book challenges. Furthermore, this work diverts her attention from her regular job.

Mrs. Gilcreast remains committed to the oath she took to honor the First Amendment by ensuring that students have the freedom to read and the freedom of choice. She argued that this process should be cut and dry: if the book is rated for the age and stage, and has literary merit- which Lawn Boy has all of- it should remain on the shelves. Mrs. Gilcreast also described the different challenges that the high school faces compared to younger levels with a larger age range. For a high school, which has students from 14 to 18 years old, there needs to be a variety of reading materials. A parent who wants to challenge a difficult book can argue that it would not be appropriate for a fourteen-year-old. “Does that mean that we only put books on the shelves for fourteen year-olds and we leave out an entire demographic? That’s not fair to those kids.”

Additionally, a New Hampshire Privacy Law states that for all minors, if a parent calls and asks what their child has checked out, the librarian is legally not allowed to share this information unless it is part of a curriculum. She stressed the importance of this law, arguing that if children need to check out books with difficult content to help them deal with difficult situations and emotions, they should be able to without fear of their parents finding out. Libraries offer unique chances for children to see themselves reflected, get a look into someone else’s life, and help themselves with challenging topics.

The six challenged books contribute to the 330 book challenges last fall alone, reported by the American Library Association (ALA), which can each include multiple books. Groups like the ALA and others are increasing their efforts to promote intellectual freedom in schools, like Mrs. Gilcreast is, as the most challenged books consistently focus on race, gender, and sexuality. The experience in Bedford this year is not unique. As Mrs. Gilcreast said, students around the country, and the world, need to see themselves reflected in the books they are reading. Books that center around white, straight, cis characters only offer the mirror she described to a select group of students, and do not offer the necessary mirror to other kids. Although each district has its own librarian, policies, and values, the book challenges in this town reflect the national conversation around student rights and free speech in schools.